Islam and Politics in France

/DR

The subject of Islam and Politics in France is quite important and interesting; especially after what happened in Paris in January last year, but also in November and in May this year, as you may all know.

In order to write this piece on the relationship between Islam and politics in France, I had to go through different literature reviews dealing with different contacts between Islam and France across history. As a French citizen, besides my personal knowledge of the situation and living conditions of Muslims in France, I also used the internet, and more particularly social media in order to grasp the atmosphere and analyse the different debates that are currently going on in France around Islam. Once again, the notions and concepts of integration and assimilation had to be studied and understood, within the French context. when it comes to Islam and the Muslim community.

The objective of this article is to give a broad view of the nature of the relationship between France and Islam, and to suggest possible tracks of research subjects that could help for a better understanding, building better social cohesion in the Hexagon.

I. Origins of the contacts and Experiences that shaped the relationship between Islam and France

I am going to develop the first part in three points.

The development of Islam and the different Muslim communities in France is due to immigration; especially that of North Africans from the Maghreb region: Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. But, also immigration from Sub-Saharan West Africa: Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, Guinea and Burkina Faso.

It’s however a mistake to analyse the relationship between Islam and France today, only from the different waves of immigration that took place in the second half of the twentieth century. My research has shown me that the first contact between Islam and France dates back to the eighth century, with the spreading of the Omayyad Empire.

a) Omayyad Imperialism

711 is known as the year marking the beginning of first contacts that shaped the relationship and image of what Islam and Muslims represent in France. I invite you to read the work of Blandine Longhi who, in her work on medieval epic songs “La Peur dans les chansons de geste (1100-1250), (2011 université Paris-Sorbonne)[1]”, also analyses and pin points through the literature of the time the imagery and conception people had of Islam and Muslim – under the domination of a Muslim caliphate. In her work Muslims are described as vigorous warriors, people of honour, and people of culture. But, at the same time, they are also people who inspire fear. I would like to ask three questions here that could be used for research: 1) In terms of citizenship, what was the status of Muslims and non-Muslims under the Omayyad ruling? 2) To what extent is it possible to make connections between the current fear of Islam in France and that fear for Muslims in the eighth century? 3) Was not the occupation of France, Spain and Portugal one of the first forms of modern Imperialism?

b) Charle Martel

The second point I would like to make, regarding the different contacts that shaped the relationship and image of what Islam and Muslims represent in France, is related to Charle Martel. Charle Martel is the son of Pépin de Herstal and the Grand-father of Charlemagne. He is the one who in 732 will put an end to the spreading of the Omayyad Empire and Islam in France[2]. To most French he symbolizes and is seen as the forefather of West European Christianity. So, the question we could ask ourselves is: “if Charle Martel symbolizes the victory of Christianity over Islam, does it not mean that the French identity was somehow forged in opposition to that of Islam?” Here is, indeed, an interesting question that could help us to better understand how Islam is, somehow, perceived today in France.

C) Colonisation and decolonisation

The third point I would like to underline here is about the process of colonization and decolonization that led to immigration. In the early nineteenth century, France starts its colonization campaign in the African continent: Algeria in 1830, Tunisia in 1881 and Morocco in 1912. The same fate will be reserved to West Africa and other black African regions. In most French colonies, indigenous are subjects. In West Africa they are also subject to forced labour until 1947. It is, however, the case of Algeria which is particularly interesting. In 1860 Algeria is then considered as a French department in which an apartheid system is applied through the Code of the indiginate[3]. People are treated differently according to their ethnicity and religion. The question to be asked here is the following: “To what extent is the current French way of dealing with Islam and the French Muslim community a legacy of that colonial period?” This question makes all the more sense that Jean Pierre Chevenement, aged 77 and known as a vigorous assimilationist, has recently been appointed chairman of a new institution that will have as a duty to regulate and work towards the integration, or assimilation, of Islam and the Muslim communities in France.

In August 2016, when appointed at the head of the organization La Fondation des oeuvres de l’islam de France “The foundation of French Islam heritage”, Jean Pierre Chevenement’s first message to the French Muslim communities was for them do their best to remain discreet.[4]

II. the French system of Integration and its specificities and limits when it comes to Islam

So, now that we have a better idea of the origins of the relationship between France and Islam, let’s move to the second part and analyse the French way of dealing politically with Islam and Muslim Ethnic minorities. In other words: “What is the French policy of integration when it comes to Islam and Muslims? What are the recently taken judicial -or political- decisions aimed at curtailing the cultural expression of the Muslim community telling us about the French system of integration? In August this year, some mayors took the decision to ban the Burkini – a swimming outfit worn by Muslim women willing to hide part of their body when at sea side. The decision of these mayors was later judged unlawful by French Constitutional Council. The questions I would like to ask here are the following: Had the international press not related the matter, and pointed out French ruling as going against Human rights, would French Constitutional Council have deliberated against these mayors’ decision? What urged, in the first place, some mayors and part of French public opinion to think that a law restraining Muslims’ dressing code in public was not illegal?

a) France is a Republic

Indeed, as former member of the HCI[5] Malika Sorelle pointed it out: France, unlike the UK, is an assimilationist[6] country; even if, the word integration which appears as more politically correct tends to be more used by politicians and journalists to refer to the welcoming and adaptation process of Ethnic minorities within society. In France, every French citizen has to assimilate with the Republic and its values. France has, indeed, been a republic since approximately the French revolution in 1789. The word republic derives from the Latin Word Res publica[7] which means “the public thing”. By public thing one should understand general interest, governing power, politics and state.

b) Secularism

After the concordat[8] of 1801, followed by decades of quarrels between the state and the different churches in France, a law on secularism was adopted in 1905. According to the 1905 Law on secularism, there should be no more intervention of the state in religious matters[9]. The law has been particularly implemented in state schools. In 1905 secularism, therefore, becomes a new value that has also to be integrated into the French notion and concept of the republic. Secularism also becomes part of the assimilating campaign of the Republic.

c) French assimilation

In the second half of the twentieth century, the first generation of Muslim immigrants tended to be rather secular and discreet, regarding the expression and practice of their Islamic cultural background. However, with the increase of the Muslim population and the second and third generations of Muslims born on the French soil, living one’s faith and expressing it openly will progressively become more common; thus underlining the limits of the French process of assimilation. Globalisation and dissatisfaction with French standards and norms can undoubtedly be accounted for the change.

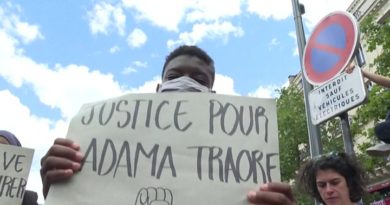

In the eighties, Muslims are the visible immigrants. They are massively lodged in the House Estate in the outskirts of France’s biggest cities, and they are consequently more subject to discrimination, police errors and other forms of racism; especially in times of high unemployment and economic turmoil. After many terrorist attacks in the US and in other West European countries at the turn of the twenty first century, many politicians -for electoral reasons but also because they are particularly attached to the “monocultural” identity of the French cultural landscape and values- will, progressively, argue against Islam and vote new laws aimed at controlling and curtailing the public expression of Islam. The acts of terrorism perpetrated by people who claimed to be acting according to the Islamic Jihad appear as a perfect argument to condemn the “religion of Mohamed” as a whole. The most famous laws or initiatives adopted working this way are: – The creation of the CCF in 2001 – the Law banning the Muslim headscarf in primary and secondary state schools in 2004 – and, the Law banning the dissimulation of one’s face in 2010 (which everyone knows aimed at Muslims, particularly). For each of these different laws limiting the cultural expression of Islam among the younger generations, arguments such as secularism, security, women’s right or again gender equality were evoked. And I ask now this question: What adjective or appellation other than discriminatory can we attribute to a political system that consistently targets one specific section of its population through new laws?

III. To be Charlie or not to be Charlie: One of the direct consequences of the institutionalized racism and Islamophobia of the French republic.

To deal with our last chapter “To be Charlie or not to be Charlie: Direct consequence of the institutionalised racism and Islamophobia of the French republic”, it is necessary to recall few definitions such as that of racism -which is not the fact of liking or disliking any particular group of people, but rather the fact of making hierarchies between people of supposed different “races” and culture.

a) Racism

One of the fathers of the theory on racism is Arthur de Gobineau, who in his work “Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races”[10], 1853–1855, tried to demonstrate scientifically the mental and therefore cultural superiority of some races over some others. His thesis will obviously be adopted and inculcated under the Nazi regime in Germany, and even in France under the Vichy Regime.

Also, according to a research done by the CNRS[11], it seems that since the end of the Second World War, we have progressively moved from a biological conception and expression of racism to one that is more based on culture and values[12]. This statement is particularly true and relevant with the way Islam is treated today in France. If “otherness” was described and identified as being Arab or black in the eighties, it is clearly proved today that in France, it is now more based on religion and values and particularly Islam. Also, the communities that formerly defined themselves as Arabs or black tend, for many reasons, to define themselves first and foremost as Muslims today. In 1983 a march “against racism and for equality” -unjustly described by some journalists as “La marche des beurres” The Arabs’ March- took place in France. It was a clear missed opportunity[13] that resulted in the creation by the socialist party of the S.O.S racism movement with its famous slogan “Touche pas à Mon Pote” (Don’t touch my mate). SOS racism, instead of sincerely fighting against racism and discrimination, played the game of assimilation, and even in some occasions that of Islamophobia. Was the same march to take place today, it would very probably be designated as the march of the Muslims.

b) Islamophobia

The term Islamophobia, which literally refers to the fear of Islam, is not officially recognized in France where politicians followed by the mass media voluntarily try to deny its existence. There is, however, no doubt that a fear of Islam exists in the Hexagon, as the laws recently passed and mentioned earlier suggest it.

c) French politicians and Islamophobia

Both major French political parties could be blamed for the tendency some Muslims have in France of defining themselves as Muslims in opposition to what they consider as being the French identity. One must not forget that it has become very common in recent years in France to hear comments from politicians that could be clearly identified as “islamophobic”. In 2009, Eric Besson, then French minister of integration, decided to open a debate on French national identity. As the general elections came closer, it, however, became clear that the debate was part of an anti-immigration campaign that mainly targeted French Muslims.

The comments of a UMP activist referring to another activist of Muslim cultural background as a good Muslim, since the latter ate pork and drank wine, was caught and diffused on social networks. What stroke most in the video was not that much the female activist’s anti-Islamic comment, but rather, the reaction of Eric Besson who, talking about the young Muslim activist, replied: “when there is just one it’s Okay, it is when there are many of them that problems start”. Eric Besson’s remark was obviously an explicit expression against the physical presence of Muslims in France; while the female activist, who called Amine a good Muslim, let us understand that cultural values were, rather, what made the difference between those part of their so called French identity and those who were not part of it.

In August 2016, during the Burkini affair, Prime minister Manuel Valls referred to a painting by Eugene Delacroix illustrating the 1830 Parisian revolt with a topless woman[14] in the forefront, saying that she represents French women: “Marianne is topless because she feeds the people! She is not veiled, because she is free! This is what the Republic is! This is what Marianne is! »[15]

His misreading and misinterpretation of the piece of art outraged many specialists and historians who, in newspapers such as Le Nouvelobs., underlined that the woman in the drawing was an allegory representing the French Republic, at a time when women were not free at all, and were not allowed to vote.[16] Manuel Valls’ comment was also judged by many as exclusive and discriminatory towards any woman who cannot physically or morally identify herself with the representation.

d) The French media and Islamophobia

French journalists also share their part of blame regarding the stigmatisation of Muslims in France. Some of them have indeed become super stars of the green screen when it comes to expressing their contempt towards the visible immigration that the French Muslim population is said to represent. Eric Zemmour, a famous French journalist of North African Jewish background, has even become an icon in the matter. On the 6th of March 2010, in Thierry Ardisson’s TV programme show ‘Salut les terriens’, he argued that: “the sons of immigrants experienced more stop & search from the police in France because most of the smugglers are Blacks and Arabs (…) This is a fact”. His comment obviously suggests that the term “immigrant”, used in France, refers exclusively to Blacks and Arabs – in other words, to Muslims. It, by the way, gives another dimension and understanding of the French general debate on immigration. It clearly demonstrates that behind the French debate on immigration, there might be some islamophobic explanations.

Other figures that are famous for expressing anti-Muslim sentiments are undoubtedly writers and philosophers Alain Finkielkraut and Bernard Henry Levy. The former is well known for his positions against Muslims youths who he says have altered the cultural identity of France. Finkielkrault,, who is opposed to the use and official recognition of the word Islamophobia in the French vocabulary, also advocates for the cultural assimilation of Muslims in France. He denounces anti-white racism and anti-Semitism coming from Muslim youths living in the French deprived suburbs. In June 2010, during the world cup, he attributed the failure and bad results of the ‘French black football team’ to the behaviour of the players, and compared the athletes to the rioting youth in the banlieues. In a radio interview, he declared: “We now have the proof that the French team is not a team at all, but a gang of hooligans that knows only the morals of the mafia”.

As to the other writer and philosopher, Bernard Henri Levy, his omnipresence on the green screen often makes people think that he is the one stirring the strings of the different successive French governments, when it comes to French foreign policy. Bernard Henri’s anti-Arab geopolitical views, and the many wars he was able to trigger in Muslim countries, have convinced French citizens of Muslim cultural background that France is the enemy of the countries they ancestors originate from. Bernard Henri Levy[17] is clearly perceived in France as the one who advocated for the involvement of the different French governments in the wars in Afghanistan, Libya, and Syria. If French public opinion first saw the riots and civil wars in Libya and Syria as outcries from people eager to more freedom and democracy, there is no doubt today, that the French Muslim community, as their other French counterparts, clearly see some kind of colonial and imperialistic motives in the involvement of the French government in these civil wars. A study of the presence of the French army on the African continent also reveals that no less than eleven countries are concerned (Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Centre Africa, Congo, Gabon, Djibouti, Libya, Somalia and etc.)[18]. Besides, the fact that the Francs CFA -which is the currency used by 16 African countries- is somehow controlled by France, and now somehow dependent on the Euro, contributes to the idea that France still indirectly colonises most of its former African colonies. This, of course, perpetrates racist feelings of supremacy over anything related to African cultural background in the Hexagon.

Other journalists also have for decades either deliberately or unconsciously suggested that French identity is opposed to that of Muslim and Vis versa. On the 13th of January 2015, few days after the Charlie Hebdo’s attack in Paris, a famous journalist, David Pujadas, was presenting the case of a French doctor who had been the victim of Islamophobia after the attacks. In a primetime news programme, he used the words “a Muslim married with a French woman” to refer to the victim. The interpellation of Najoua Arduini-El Atfani, the president of the OrganisationClub du 21e siècle, who was one of the members of the public in a TV programme show presented by the same journalist some few days later, was a perfect demonstration of how the use of words in the mouth of both politicians and journalists can sometimes play a divisive role in society. Najoua Arduini-ElAtfani made it clear that words matter, and that David Pujadas should not have described the victim as “‘a Muslim’ married to a French woman”, since both of them are French nationals[19].

CL: When Islamophobia leads to chaos

France’s extreme expression of Islamophobia is clearly illustrated through the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. The Charlie Hebdo newspaper has, for decades, been using the same techniques, formerly used against the Jews in the first half of the twentieth century to create and foster anti-Semitism. Caricatures illustrating someone they call the prophet of Islam, in insulting situations and positions, are often published by the Charlie Hebdo newspaper; which, obviously, provokes the indignation of most Muslims who judge the drawings racist and Islamophobic. At the same time, the judiciary measures and condemnations pronounced against comedian Dieudonnée M’Bala M’Bala, for his jokes against Zionists’ philosophy, clearly show the existence of a double standards phenomenon when it comes to freedom of speech. Besides experiencing discrimination in jobs and housing, Muslim youths have also the feeling of being constantly pointed out and insulted by those whose duty it, normally, is to open consciousness and work towards better social cohesion. In such conditions, it becomes clearly easy for young Muslims to define themselves in opposition to the system they think oppresses them.

It is consequently in January 2015, that the failure of the French assimilationist system finally came to the daylight. The murder of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists by some French young citizens who claimed to have avenged the Prophet of Islam through their act shocked the whole nation. Solidarity and compassion were without limit. An international march was even organized in Paris under the slogan “je suis Charlie”. If everyone condemned the barbaric crime, it was, however, interesting to notice that many media recognized and made the link, for the first time, between the attack and the excess of stigmatization on Islam, in a society where discrimination very much explains the poor social conditions of most young people of Islamic cultural background. The fact that the few people who escaped the second attack in a Kosher shop were saved by a Malian residing illegally on the French soil; while the perpetrator of the crimes on that day was a young man born and raised up in France -but of Malian cultural background-, could not be better testimony of the failure of the French system of integration.

Fin

[2] William Blanc et Christophe Naudin, Charles Martel et la bataille de Poitiers. De l’histoire au mythe identitaire, éditions Libertalia, 2015 (ISBN 978-2-91805-960-8)

[4]http://www.lefigaro.fr/actualite-france/2016/08/15/01016-20160815ARTFIG00078-chevenement-conseille-la-discretion-aux-musulmans.php

[5] Haut Conseil à l’Intégration (The institution created under president Sarkozy was dismantled in 2012)

[8]Agreement between the Church in Rome and the French State: https://www.histoire-image.org/etudes/concordat-1801

[9]http://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/contenu/piece-jointe/2014/07/note-d-orientation-la-laicite-aujourdhui_0.pdf

[11]CNRS: Centre National de recherché scientifique

[14]Liberty leading the people

[15]“Marianne a le sein nu parce qu’elle nourrit le peuple ! Elle n’est pas voilée, parce qu’elle est libre ! C’est ça la République ! C’est ça Marianne !”

[16]http://leplus.nouvelobs.com/contribution/1554954-sein-nu-de-marianne-manuel-valls-a-tout-faux-c-est-une-allegorie-de-la-republique.html